Telling Tales: The Story of Victorian Narrative Art. Exhibition at the Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery, Bournemouth (until March 5th 2023) and then Southampton City Art Gallery (17th March – 9th September 2023)

Curated by Kirsty Stonell Walker

Review by William Rose.

The Victorians liked a story to go with their paintings. A whole range of them from the ancient sources of mythology and the Old Testament to the literature of the great poets and to the contemporary depictions of the ecstasies and tragedies of romantic love. And the hardships of life could be impressed upon the more affluent viewer through images of the cold realities of poverty and social distress.

The tales from the myths and from fairy stories had the familiarity of archetypal themes, and the drama of literature presented characters that could be recognised from many told stories, whilst other works rested upon inference, with stories that were to be imagined. And there was also the coded meaning of symbols, not to be inferred, since this was a concrete symbolism, most often pertaining to flowers, each variety with a direct line to a virtue or emotion.

The exhibition now showing at the Russell-Cotes Museum in Bournemouth (and later at Southampton City Art Gallery), is ‘Telling Tales: The Story of Victorian Narrative Art’ and it takes us on a tour through the narratives in an era of fine art in which the story took on a fresh significance.

Though substantial, this is not a large exhibition, and can be comfortably viewed in an hour, though it might well beckon the viewer to stay longer, or to visit again. It is not possible to mention every painting, so a few that are indicative will be described here.

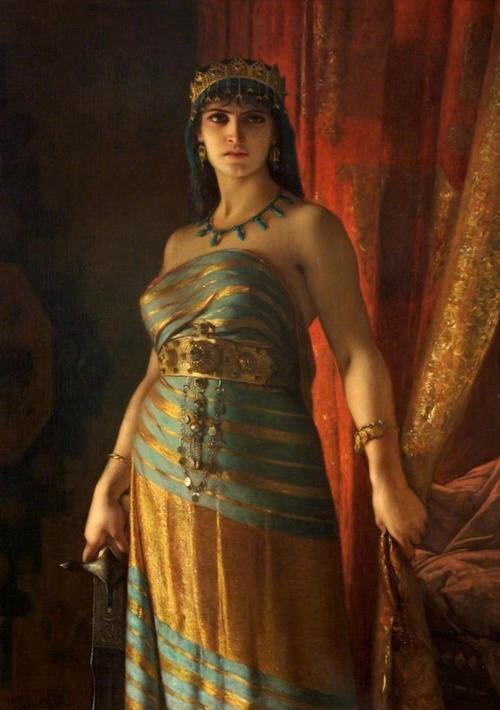

On entering the show, there is, immediately, a magnificent ‘Judith’. One of many great paintings that have derived their often, gruesome splendour from the Old Testament tale of Judith and Holofernes, but let us save her for the finale.

We turn left into the section ‘Love and Life’.

There is much evidence of the trials and tribulations of love for the woman – as the betrothed, the wife, and the widow. This seen through a modern-day awareness and historical reflection, but it was also in the intention of artists of the time.

‘Despair’. Frank Holl. 1881. Southampton City Art Gallery.

For both ‘Hope’ and ‘Despair’ there are two paintings by Frank Holl. In ‘Despair’ there is nothing kept in reserve; this is just what it says and is a scene that can only be of utter loss. The female figure is overwhelmed in the loneliness of grief, whilst the girl child who stands observing can only watch with helplessness and the unknowingness of her age. In this, the depiction of the child’s face is brilliantly done. The painting, utterly grim.

Frank Holl. ‘Hope’. 1883. Southampton City Art Gallery.

In ‘Hope’, we can only hope that the hope shown is well placed. A family, clearly in poverty in the rough stone interior of their cottage, are waiting. The mother gazing through the window. Is her husband a fisherman? It seems probable, and it is also probable that if he has died at sea the family will be destitute. Holl is described as ‘The dour father of social realism’. His critics said he was only concerned with ‘starvation, coffins and the dock’. But he could certainly tell a story and paint a picture.

Frederick William Eiwell. ‘Mischief’. 1901. Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery.

Frederick William Eiwell’s ‘Mischief’ of 1901, is a wondrous pastel. I was amazed to see that that was the medium. Given the title, we are urged to believe that mischief is afoot, to be manifested in some form by the young woman whose portrait is the painting. But that is the thing about a title. It leads us towards a prescribed place. Without the title this could be a magnificent portrait with exceptional warmth, and the slight smile which is also, wonderfully, in the eyes, could be the expression of warmth within – happiness and fond thoughts – intimate times remembered – and just perhaps, with some mischief included. The engagement / wedding ring, so provocatively displayed, must also be part of the story.

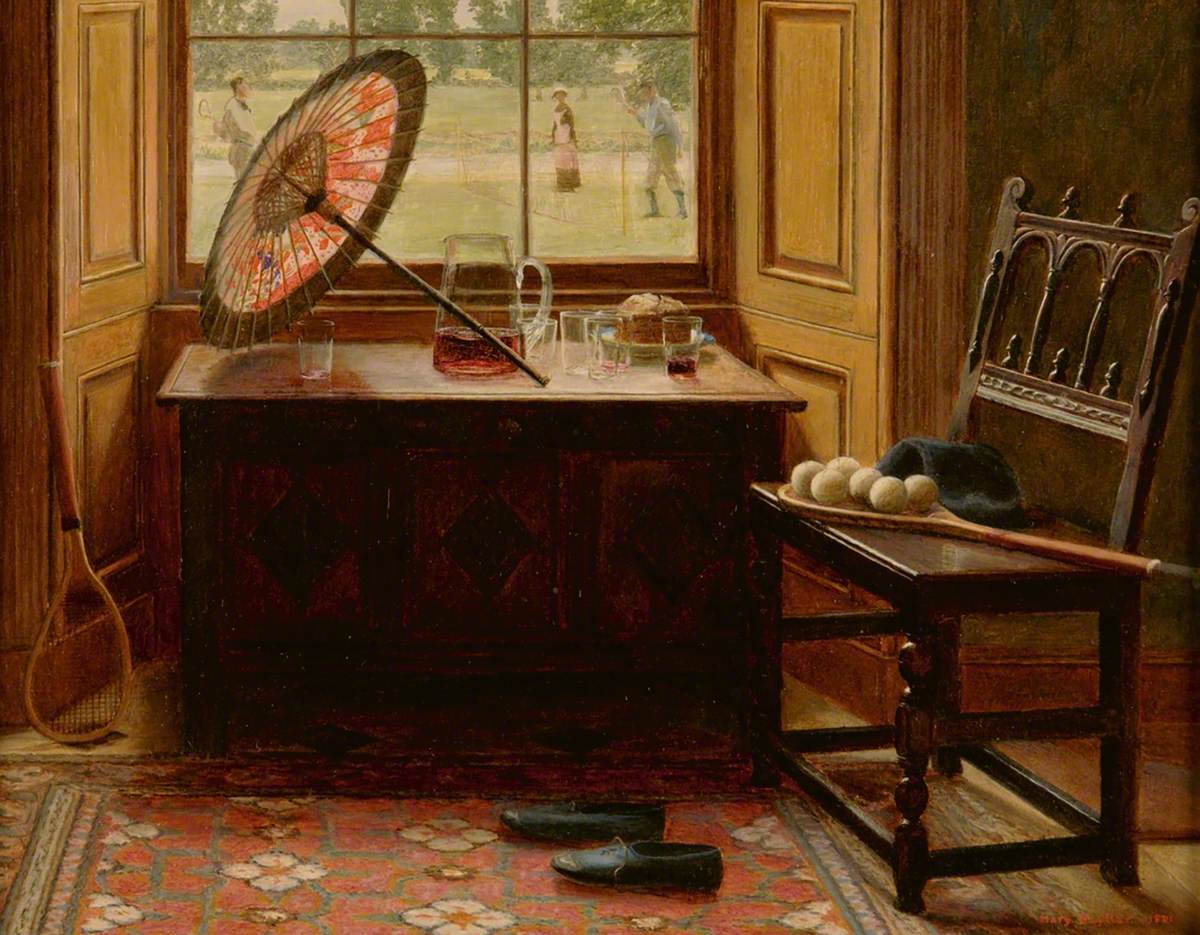

Mary Hayllar.’The Lawn Tennis Season’.1881. Southampton City Art Gallery.

There is a delightfully rendered and detailed little oil painting by Mary Hayllar, ‘The Lawn Tennis Season’ of 1881. The tennis, on its lawn, is seen brightly through the window of a room which conveys that sense of a quiet, shaded interior whilst the warmth of Summer permeates the scene outside.

Frank Cadogan Cowper. ‘The Fortune Teller, Beware of a Dark Lady’. Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery

Frank Cadogan Cowper’s ‘The Fortune Teller, Beware of a Dark Lady’, is suffused with ominous narrative. The title aids the imagination and the imagery does the rest. The painting is strong in depiction of its characters and also stands out from those around it as one of a different era. The work is of 1940 but owes its Victorian inclusion to the memory of the artist as he looks back to events from forty year before. Two women are facing the viewer. One, blonde and in white with red roses, is in full confidence as she looks straight outwards. But surely, she will suffer from the malevolent wishes of the ‘friend’ with veiled eyes and dark intentions. The fortune teller kneels by the woman in white and gives her warning – the title of the picture.

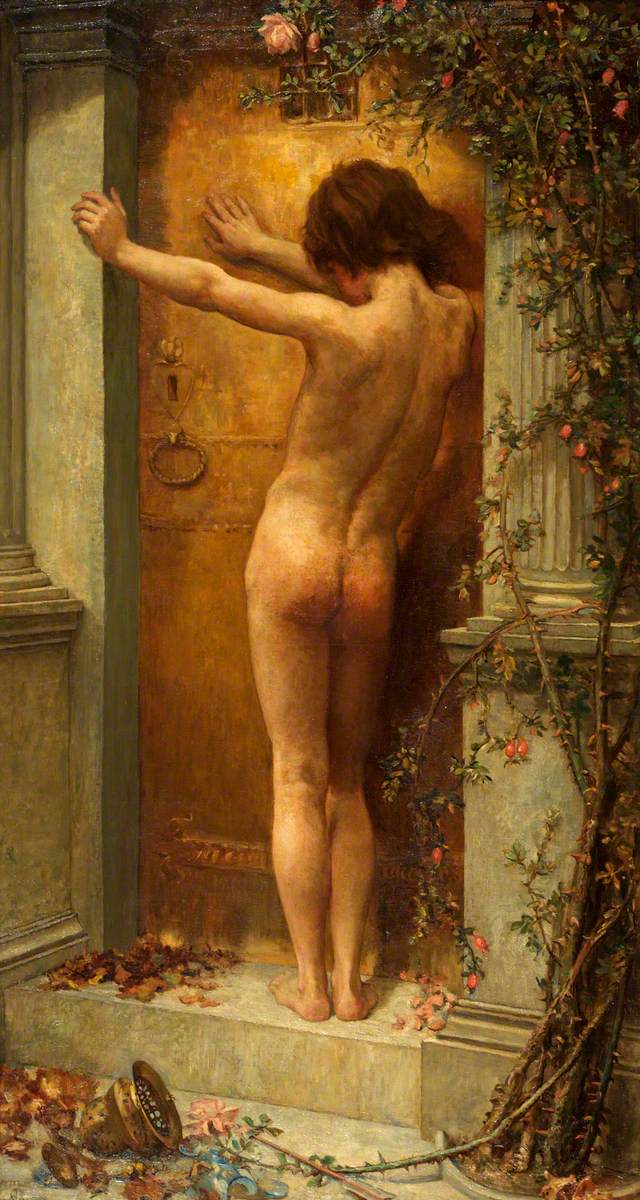

Henry Justice Ford. Copy of Anna Lea Merritt. ‘Love Locked Out’. 1890. Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery.

In ‘Love Locked Out’ the tragedy has already occurred. It is a well-known image, with the original by Anna Lea Merritt (1890). Sir Merton Russell-Cotes commissioned Henry Justice Ford to make a copy. An abandoned Cupid, who in turn, has now abandoned his arrow and lamp, is barred from entering a door, his despair no longer allowing any creation of love. It is the doorway of a tomb and there has been a death: love for the one left alive is now over. Anna Lea Merritt’s husband died two months after her marriage in 1889. It is, therefore, a deeply personal narrative of personal loss, using mythology for its imagery of great sadness.

Indeed, misfortune in life and love colours much of the work in this section and is included in the exhibition’s descriptive texts. We see how unfavourable were these times for women, who could be so dependent on marriage and their husbands for their honour and survival, though in the narrative of ‘Love Locked Out’, loss of actual love is reassuringly, albeit tragically, present. There could be love matches.

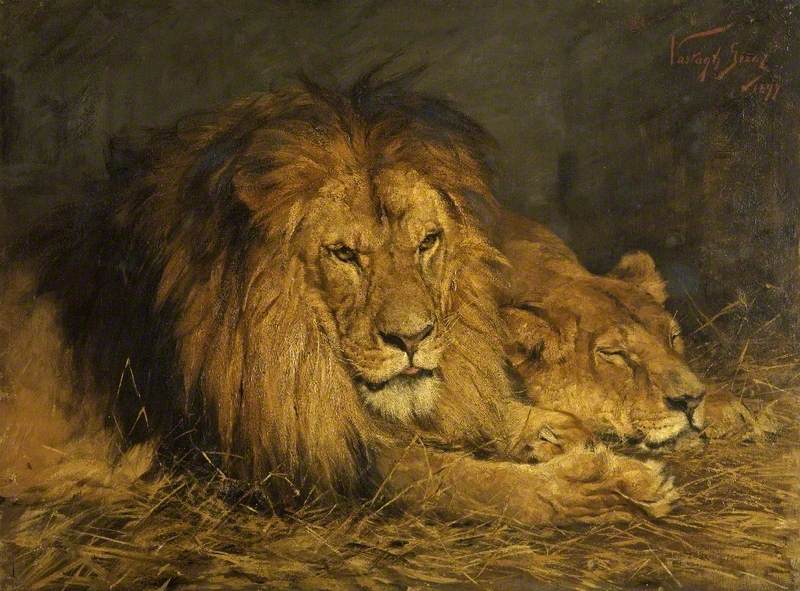

Géza Vastagh. ‘Repose, or the British Lion’. 1899. Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery.

The next section of the exhibition is ‘Beasts and Babies’. There is here amongst the beasts, the magnificent painting of a lion couple, ‘Repose, or the British Lion’ (1899) by the Hungarian, Géza Vastagh. Absolutely enough to give anyone confidence in being British – who could ever overwhelm such powerful beasts, the male lion particularly. But why should a Hungarian artist be so proud to be British? Well, he did not have to be. ‘The British Lion’ was added to the title by Pears Soap Ltd who had bought the painting. We can imagine that for Vastagh it was still just its original title ‘Repose’, and can be enjoyed as a terrific painting of magnificent animals, though that might do away with the narrative.

George Sheridan Knowles. ‘Her First Love’. 1865. Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery.

There is a beautiful portrait of a young girl, showing all the devotion that some Victorian male artists could give to this subject. Rather a British thing. It is by George Sheridan Knowles from 1865 and is titled ‘Her First Love’ and that first love is the pet rabbit that she cradles in her arms. So, as we imagine the narrative – if this is the first love, what is to follow? I found the accompanying text to this one a bit pessimistic. The title of the painting apparently draws on a popular play of the time, ‘The Love Chase’ by James Sheridan Knowles. There are lines quoted:

‘Not on superficial grounds she’ll ever love / But once she does the odds are ten to one / Her first love is her last.’

The exhibition’s accompanying text takes from this that there might never be a love to match the young girl’s love of her pet. But could it be that when she loves as an adult it may be a love that is undying, and certainly not superficial? But perhaps I am overly optimistic. But with such subjects the subjectivity of the viewer must also have credence. The paintings are there to stir the imagination.

Most of all, I see this as a gentle meditation on the oncoming loss of childhood. Love for pets and toys will be usurped by the inevitable forces of sexuality, something that gives an edge to the painting’s sentimentality.

Clementina Margaret Hull. ‘The Thief’. Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery.

There is a very pretty watercolour by Clementina Margaret Hull of that much maligned bird, the magpie. And in accordance with its bad character, the title is ‘The Thief’. The narrative here is manifestly of a theft, as the bird, standing upon a table, clasps a shiny necklace in its beak. A great opportunity, as well, for the artist to make a lovely watercolour of the bird within a picturesque and very decorative, still life. There is more narrative than that if you know the reference, “Then It Chanced in a Nobleman’s Palace That a Necklace of Pearls was Lost”. It comes from an 1847 poem ‘Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie’ by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882).

William John Hennessy. ‘Penance’. 1889. Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery.

On moving into ‘God and Generals’, one is confronted by a huge painting of staggering, moral cruelty. This could also have been in the ‘Love and Life’ section as the ultimate in destitution when a love has been condemned. This love has brought forth an infant, and both unwed mother and her baby are condemned to the ‘Penance’ of the title. In just a smock, holding a candle, her infant clasped within her arm, she walks barefoot in a desolate winter landscape. Her hair hangs loose about a face that for the intended viewer, expresses due penitence. Very grim and who could have possibly wished for this on a wall of their home. It would be interesting to know the painting’s history of ownership. It is by William John Hennessy, 1889.

John Everett Millais. ‘Flowing to the Sea’. 1871. Southampton City Art Gallery.

There is an unusual Millais painting, ‘Flowing to the Sea’. Very large, and seeming to want to be a landscape, though there are some figures who have been placed at the sides and who provide the narrative. They are soldiers and the red of their uniforms makes a splendid feature against the greens of the landscape and the bright blues of the river and the sky. One soldier bids farewell to his milkmaid lover, and the inference is, surely, that the farewell may be forever.

Allan Stewart. ‘To the Memory of Brave Men’. 1897. Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery.

There is, in this section, the pride of empire and its romanticism, especially the glory of defeat. ‘To the Memory of Brave Men’, but in full ‘To the Memory of Brave Men’: The Last Stand of Major Allan Wilson at the Shangani, Rhodesia, 4 December 1893’ rivals Custer’s last stand at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. It is a replica of the original of 1896. The subject must have had special appeal for Sir Merton Russell-Cotes as he commissioned this signed copy by the artist, something that he did with other works when he really liked them and was not able to obtain the original. (‘Love Locked Out’, above, was also commissioned as a copy).

John Charlton. ‘The Awakening’. 1916. Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery.

Almost at the end of my circuit, I arrived a great big painting, hugely extrovert and theatrical. Fire and damnation is imminent, at least for some. The painting is divided into hell in the lower half and rightness above. Justice is there at the top, brandishing her scales with all the appearance of a severe mistress. Cruel mistresses were not unknown to some in the Victorian establishment. A half-nude figure presides over the damnation scene below, which, despite its hellishness, seems somewhat more interesting than the virtuous realms above.

But my contemplations about this painting, which is ‘The Awakening’ by John Charlton (1916), had to be tempered when I read the accompanying text. It was made as an allegory of the First World War, with the Allies, the defenders of justice and the Germans being banished to the pit of hell. “Those that dig pits of destruction for others will fall into them themselves”. From Psalm 35.8. A very apt quote for our present time. The extreme treatment of the subject becomes understandable as Charlton’s two sons died in combat within a week of each other in 1916. Now, the painting can be seen as one of utter rage and grief.

Charles Landelle. ‘Judith’. 1887. Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery.

And so, to return to Judith, who stands near the space that is both entrance and exit to the exhibition. A star in the Russell-Cotes collection by the excellent French painter, Charles Landelle. You certainly don’t mess with this woman. The familiar narrative is conveyed without contrivance through the expression, posture and triumphant attire of the subject. At the bottom right she holds a sword that is relaxed in her hand. It points downwards; nothing is brandished, as if the deed is done. With the other hand she pulls aside a curtain, just to give a glimpse of the room behind, and which is only a suggestion, an inference, to the presence there of her enemy, the Assyrian general, Holofernes. The narrative might say that he is there, unconscious of his fate and imminent beheading, but I prefer to see this as the deed already done. No need for blood or severed heads. She has successfully accomplished her mission. A crown is upon her head.

The Exhibition continues at the Russell-Cotes Museum and Art Gallery, Bournemouth, until March 5th (2023) and then moves to Southampton City Art Gallery, March 17th – 1st July (2023).

Well worth a journey.